How the mystery of Mercury and Vulcan laid the path for a scientific revolution

On May 8th, 1845, Mercury was sixteen seconds late. Like its divine namesake, the solar system’s innermost planet was a problem child. Ever since Isaac Newton had formulated his laws of universal gravitation and motion, astronomers had been building tables of the exact orbits of all the planets. Using ever more subtle and nuanced understandings of the laws, they had succeeded — for the most part. They still couldn’t pin down Mercury, despite all the other planets having become subject to human understanding. Not that there hadn’t been challenges before. French astronomer and mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace had explained the observed changing orbits of Jupiter and Saturn, out of line with Newtonian expectations, by more exact calculation.

But Mercury was proving a more difficult problem. It was particularly vexing for Urbain Jean-Joseph Le Vellier, Laplace’s successor as France’s preeminent astronomer-mathematician. His tables, predicting a transit, that had foretold Mercury would arrive before it did. This was a direct challenge to Newton. His laws were supposed to be universal — they were the same everywhere on Earth and throughout the heavens. To say otherwise was blasphemy.

Le Vellier, a proud Newtonian, would continue returning to the problem of Mercury for the next decade-and-a-half. He couldn’t devote his whole time to the planet though. Another problem was plaguing astronomers. On the outer edges of the known solar system, Uranus, the only planet up to then discovered since the ancients, was also misbehaving. Le Vallier’s solution would lead him to suspect a similar solution to the Mercury problem. By calculation, pen and paper, he was about to discover Neptune.

If there was an unseen planet outside the orbit of Uranus, maybe there was one inside that of Mercury’s. Le Vallier’s solution was Vulcan — a boiling planet, first in line to be hit by the Sun’s immense heat and power. There was only one problem. Vulcan didn’t exist. And yet, Mercury was late.

Before 1781, William Herschel would have thought he’d be remembered for his music, if anything. But he would go down as the man who discovered the first planet that the ancient Babylonians, Egyptians, Greeks and Romans had missed. On March 13th, 1781, he rushed away from his job as director of the Bath Orchestra to his great passion, astronomy. He was on the hunt for true binaries, stars that orbited one another rather than appeared to be paired by being on the same sightline from Earth. He pointed his telescope at one such potential binary, between Tauros and Gemini, and saw something unexpected.

At first, Herschel thought it was a comet. Many had been spotted before. He watched it over the course of the next month, but it did not behave like a comet. There was no tail. It didn’t alter in size. It appeared as a fuzzy disc and he noted its gentle arc across the night sky. From his observations, others worked out a rough path. It orbited the Sun. It was a planet. It was Uranus.

Here was a test of Newton. Would his laws be able to precisely describe the behaviour of such a novelty? To get a better fix on Uranus, astronomers explored their archives. They discovered misidentified sightings of it before, dating back to 1690. With a rough plot and observations from both before and after Herschel’s discovery, by 1821 they were able to describe its track around the sun. But what they had come up with didn’t line up with Newtonian predictions. Something was wrong.

By 1845, the problem of Uranus was an embarrassment. This was the task given to Le Verrier. He began by recalculating the supposed orbit, refining it to a point where he has sure something else was to blame. Could an asteroid hit have whacked Uranus out of Newtonian perfection? Did Uranus have a moon pulling it out of its predicted orbit?

Le Verrier rejected these possibilities. Something else was out there. Eliminating some variables and making some assumptions, he was able to reckon where a possible culprit lurked. It was 1846, a mere year after being set this mathematical mystery. By August 31st, he was able to report where in the sky someone should look to spot it. No one did. His colleagues in Paris were uninterested. They didn’t have the right equipment or up to date star charts. They wouldn’t know what they were seeing even if they had trained their telescopes to the point east of Capricorn where Le Verrier thought the planet was hiding.

Over two weeks later, Le Verrier’s frustration got the better of him. If Paris wouldn’t look for his planet, some other observatory would. On September 18th, he wrote to Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory. Five days letter, Galle received the letter. That night he pointed his telescope at the small square of sky. An assistant, Heinrich Ludwig d’Arrest, ticked off known objects on a star map. Just after midnight, Galle called out one speck of light. It was not on the map. Neptune had been found, in the word’s of the head of the Paris Observatory, ‘on the tip of [Le Verrier’s] pen.’

Le Verrier became famous. All Europe celebrated his achivement. He toured the continent, taking in awards and honours. That victory lap, a power struggle at the Paris Observatory and the 1848 revolutions kept him from returning to the problem of Mercury.

Neptune had been found, in the word’s of the head of the Paris Observatory, ‘on the tip of [Le Verrier’s] pen.’

In 1852, Le Verrier came back to his larger work, determining the precise orbits of the inner planets and showing that they were stable. This produced results. He was able to find that the previous estimates of the Earth’s distance from the Sun were wrong. His corrected result was impressively close to modern measurements. He re-reckoned the mass of the Earth and Mars. With these, he was able to fix the orbits of Venus, Earth and Mars. All were in line with Newton’s laws. Mercury, however, was still misbehaving.

The problem was small. Mercury’s perihelion, the point at which it is closest to the Sun, was inching forward. The planets out to Jupiter accounted for a good part of that creep. But there was a tiny sliver left — an accounting error that shouldn’t exist. It was miniscule. Over three million years, Mercury would make one more orbit than anticipated; over a year, that was merely .38 arcseconds of difference or around 1/10,00th of a degree.

With his rigourous calculations in hand, Le Verrier knew that either Newton’s laws were wrong or there was something else propelling Mercury onwards. And Newton wasn’t wrong. On September 12th, 1859, he published his results. He initially thought that it was an intra-Mercurial asteroid belt, believing a planet with enough heft able to create such an acceleration would have been spotted before. On December 22nd that year, a letter was sent that would change his mind.

Edmond Modeste Lescarbault was a French country doctor but, like Herschel, his passion was astronomy. Unlike Herschel though, he was on the search for asteroids. He had watching in 1845 when Mercury was late. One of the best ways to spot asteroids is when it makes a transit, or crosses the Sun’s face when viewed from Earth. Le Verrier’s calculations had yielded the best yet calculations for when Mercury would transit the Sun — an appointment it was 16 seconds late for.

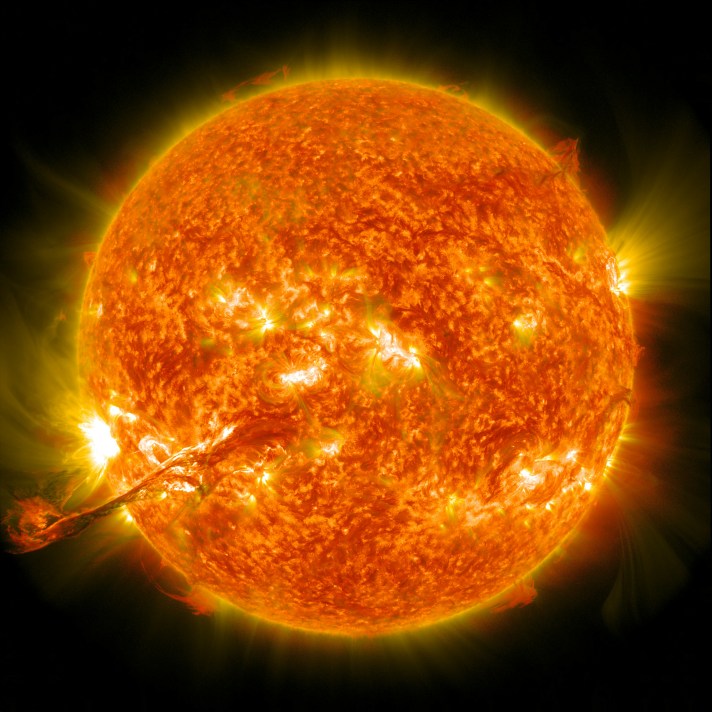

Lescarbault continued watching for transits. On March 26th, 1859, he finally spotted one. Between seeing patients, he would take snatches of time at his telescope. That day, he saw something roughly a quarter the size of Mercury cross the Sun. He was not present for the whole transit but worked out it lasted one hour and seventeen minutes. He didn’t do anything with this observation though until he saw a report of Le Vellier’s work later that year. Finally, on December 22nd, he wrote to Europe’s most famous astronomer, convinced that what he saw was a planet.

Le Verrier raced down to Lescarbault’s little village outside Paris. He was convinced after questioning the diligent, if amateur, Sun watcher. In January 1860, with Lescarbault’s observation backing up his calculations, he announced that he had found Vulcan.

This announcement was treated with the same fanfare as his discovery of Neptune. He was feted across the world. He was elevated to the status of a scientific god, an unrivalled genius. His name is little known today, despite his mathematical heroics to uncover the shadowy Neptune.

Vulcan didn’t exist. Attempts to back up Lescarbault’s observation and Le Verrier’s calculations did not succeed. As with Uranus, astronomers once more opened up the archives looking for hints at previous, unrecognised sightings of Vulcan. These may have been identified as sunspots rather than as a new planet. With several candidates identified alongside Lescarbault’s observation, work was done to predict when the shy planet would transit the Sun and could be seen again. With such few data points to work with, this was imprecise. But despite diligent work, with continuous stakeouts looking at the Sun over the course of days and weeks, Vulcan did not make an appearance.

The best chance to spy it would be during a solar eclipse. One would come in 1869 in America. Armed with the latest technology, photography, many US observers were ready to lay claim to ironclad proof that Vulcan existed. One early pioneer of astrophotography, Benjamin Gould, would take his own photos as well as comb through around 400 others. None showed Vulcan. But it was not yet dead. If Newton was right, as he had been up to then, than Vulcan, or something like it, should exist. The math said so. In 1878 there would be another eclipse and another chance to see Vulcan.

Even with better and better telescopes, cameras and methods, it did not show itself. Less than two decades earlier, Vulcan was placed among the planets in textbooks. Now, Mercury’s unexplained creep and Vulcan’s inability to materialise were becoming embarrassments.

So, it was ignored. Le Verrier died in 1877, still believing he discovered two planets. The eclipse of 1878 put that assumption under extreme strain. By the turn of the century, people believed in Newton’s laws but not in the planet that they said should exist. It became an oddity, an aberration, something better left unspoken.

Mercury’s unexplained creep and Vulcan’s inability to materialise were becoming embarrassments.

It would take a mind equal to Newton’s to work it out and revolutionise physics. Albert Einstein would do so.

For Newton, gravity just was. He didn’t provide any hint why it should be so. He measured it, distilled how it worked and produced his laws. Einstein saw that time and space are linked. Mass warps it. Where it is concentrated, near the Sun for instance, it creates deep gravity wells. Newton’s laws, outside of such wells, describes how gravity works nearly perfectly. In them, his laws buckle and break.

For Einstein to prove his new conception of gravity was correct he would need to prove Newton wrong. There were a few false starts. In 1914, he announced a preliminary account of his theory, but that still couldn’t account for the excessive wandering of Mercury. The first world war did not interrupt Einstein’s work but allowed him to refine his thoughts. It was hard work, the most intense of his career as he would later recall. But he got there. He showed that his theory would replicate Newton’s laws, for the most part. It was near the centre of the solar system that things broke down. He would soon fix it.

On November 18th, 1915, near the end of a series of lectures he was giving to the Prussian Academy on the progress of his work, Einstein outlined how his new ideas about gravity could explain why Mercury’s perihelion was inching forward. Vulcan was not needed. Only a completely new understanding of how space, time, mass and energy interact was. Newton, it turned out, was wrong.

Science is supposed to progress through observation, hypothesis, prediction, theory and experimentation. If theory disagrees with observation, than the theory is wrong. For half a century, physicists ignored this when it came to Mercury. Newton was always right, they believed.

Thing are never as perfect as they are described. The problem of Mercury should have alerted scientists to issues with Newton’s laws — at least in extreme cases. But to do so, they would have to throw out their whole conception of how the universe worked. It was a problem not many could face and fewer overcome.

Thomas Kuhn, an American philosopher, distinguishes between normal science and a paradigm shift. The shift from Newtonian gravity to Einstein’s general relativity was one such shift. Normal scientific work can show when an established framework is wrong, but it takes something else to create a new paradigm. For half a century, Vulcan was ignored. Now it is mostly forgotten. But it highlights how far from certain all our scientific knowledge about the world is. It is not as solid as it is made out to be. It moves and shifts; we must be ready and able to shift with it.

Read more

The Planet That Wasn’t, Isaac Asimov

In Search of Vulcan, Robert Fontenrose

The Hunt for Vulcan, the Planet That Wasn’t There, Simon Worrall

Why Everyone Went on a Wild Goose Chase Looking for the Planet Vulcan, Kat Eschner